Where Do We Go From Here?

Examining the Role of Public Art in Preserving Two Black North Carolina Neighborhoods Affected by Urban Renewal

A Public History Project by Anthony Patterson

Urban renewal, as defined by psychiatrist and scholar Mindy Fullilove, is the process of “destroying neighborhoods under the pretext of renewal,” often leading to what she terms "root shock"—the psychological trauma that individuals and communities experience when they are forcibly displaced from their homes (Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It, 2004). This process was legally sanctioned by the Housing Act of 1949, which provided federal funding for slum clearance, land redevelopment, and highway construction. While marketed as a means to modernize cities and improve infrastructure, urban renewal disproportionately targeted Black communities, erasing historically significant neighborhoods and displacing thousands of residents under the guise of progress.

In North Carolina, urban renewal reshaped the landscapes of Charlotte and Durham, leaving lasting scars on Black communities. Durham’s East-West Expressway (now NC-147) devastated Hayti, once a thriving center of Black business, culture, and education. Established in the late 19th century, Hayti was home to North Carolina Central University, Mechanics and Farmers Bank, and countless Black-owned businesses. However, between the 1960s and 1970s, urban renewal projects razed nearly 200 acres of Hayti, displacing more than 4,000 residents and demolishing 600 Black-owned businesses. Today, remnants of Hayti exist only in fragments, overshadowed by modern development projects.

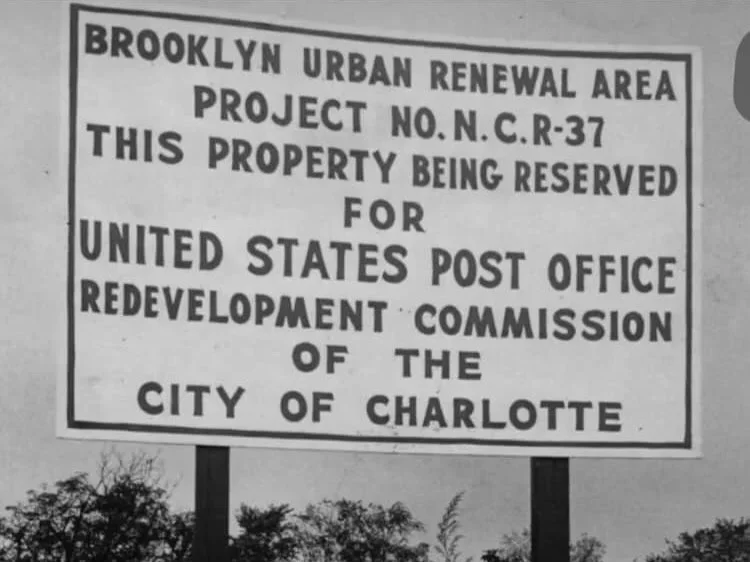

Similarly, Charlotte’s Brooklyn neighborhood, located in the historically Black Second Ward, was a vibrant community that flourished throughout the early 20th century. It was home to schools, churches, businesses, and the cultural elite of the Black community in the city. However, in the 1960s, the construction of Interstate 77 (I-77) and aggressive redevelopment efforts led to the destruction of Brooklyn. By the time urban renewal was complete, over 1,000 Black families had been forced out, with little to no effort made to relocate or support them.

Today, Hayti and Brooklyn exist mainly in memory, with fragments of their histories preserved through oral histories, archives, and scattered historical markers. Public art—including murals, sculptures, and installations—has become a powerful medium for reclaiming these lost narratives in recent years. Artists, preservationists, and community members are working to ensure that these once-thriving neighborhoods are not forgotten, using art for cultural preservation and historical justice.

I argue that public art is an essential first step in restoring community history and a catalyst that encourages dialogue within communities to advocate for neighborhood improvements, such as better infrastructure, historical markers, and cultural spaces. Through oral histories with preservationists, artists, and displaced families, this research will examine the challenges, benefits, and opportunities that public art presents in shaping collective memory. By understanding how visual storytelling can honor displaced communities and inspire advocacy, this study will identify tangible steps to ensure that these neighborhoods’ histories remain visible, even as Charlotte and Durham evolve.

Contact us

Interested in working together? Fill out some info and we will be in touch shortly. We can’t wait to hear from you!