Abel Jackson

It all begins with an idea.

In my conversation with Charlotte-based artist Abel Jackson, public art emerges as more than a visual expression. It functions as a method of historical engagement—one rooted in listening, research, and long-term relationship building. Jackson’s mural practice offers a lens through which to understand how Black communities have preserved memory and meaning in the wake of displacement, particularly through urban renewal.

This interview contributes to Where Do We Go From Here? by connecting artistic practice to broader questions of place, loss, and resilience. Through Jackson’s reflections, public art becomes a site where history is not only represented, but actively negotiated in the present.

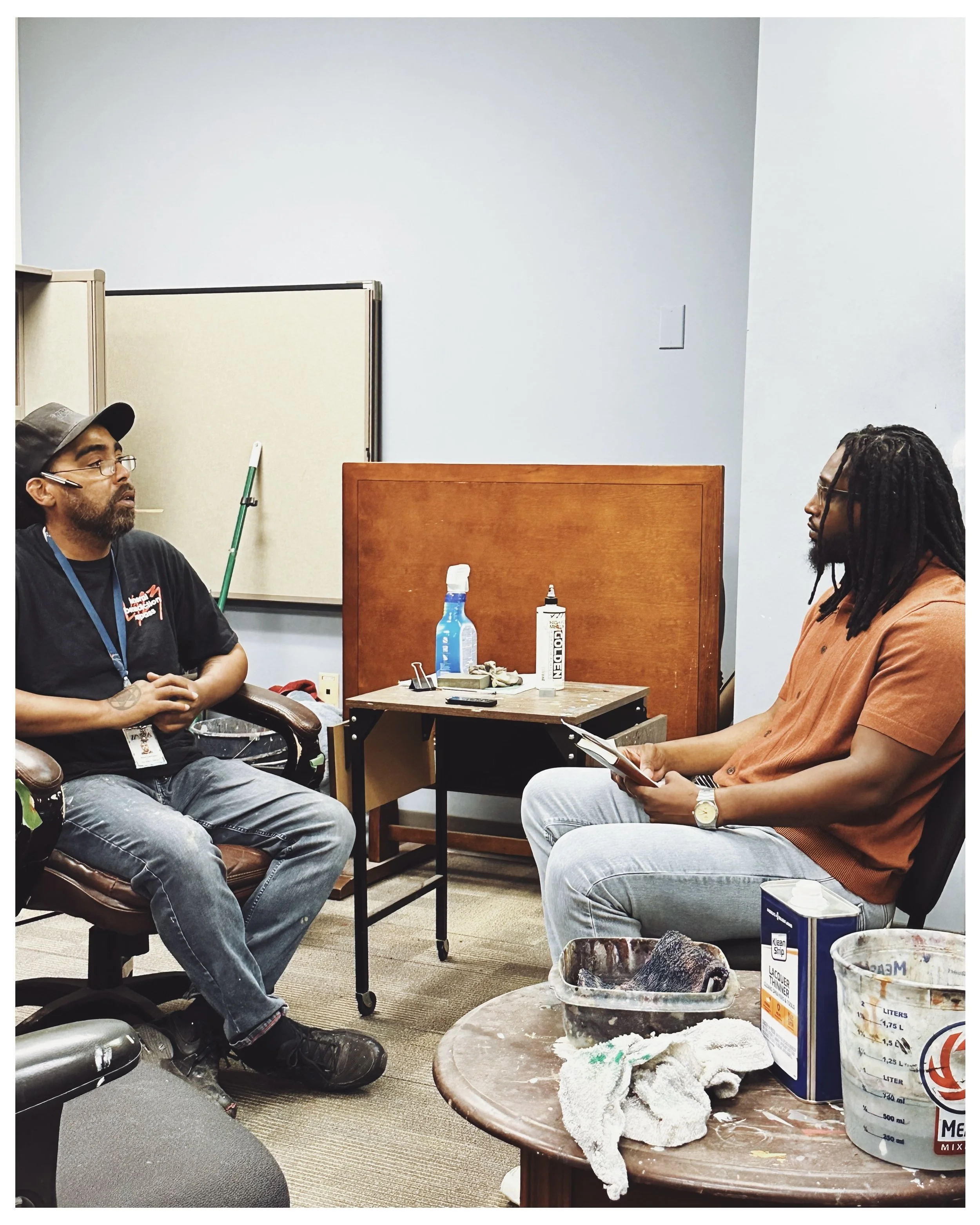

Abel Jackson and Anthony Patterson in his studio in Charlotte, NC

Public Art as Relational Practice

Jackson describes his entry into public art not as a sudden shift, but as a natural extension of years spent working as an artist in Charlotte. Beginning his career in 2002, he moved into public art around 2012 through relationships built over time. These connections—with individuals, organizations, and communities—shaped both the opportunities he received and the way he approaches his work.

For Jackson, public art begins with conversation. Before design or painting takes place, he emphasizes the importance of listening to the people connected to a site or project. This process allows murals to reflect not just a singular vision, but a collective understanding of place. In this way, public art operates as a shared endeavor rather than a detached commission.

This approach closely mirrors the methodology of this project, which treats community knowledge and lived experience as essential historical sources.

Brooklyn and the Reframing of “Negro Wall Street”

A central focus of the interview is Jackson’s mural work connected to Brooklyn, a historically Black neighborhood in Charlotte that was deeply impacted by urban renewal. Through his research, Jackson came to understand Brooklyn as part of a much broader historical pattern—one in which Black communities across the United States developed systems of economic independence, mutual aid, and institutional completeness.

Rather than viewing “Negro Wall Street” as a singular exception, Jackson reframes it as a widespread reality. Brooklyn, like many Black neighborhoods, supported its residents through locally owned businesses, professional services, churches, schools, and social networks. These systems allowed communities to thrive despite segregation and structural exclusion.

Urban renewal disrupted this ecosystem. Jackson describes displacement not simply as the loss of buildings, but as the dismantling of interconnected ways of life. His reflections help situate Brooklyn within a national story of Black self-determination and targeted removal.

Murals as Open Doors to History

Jackson makes a clear distinction between public art as historical documentation and public art as historical invitation. Rather than attempting to tell a complete story, he views murals as openings—visual prompts that encourage curiosity and engagement.

In this sense, murals do not replace archives, oral histories, or written scholarship. Instead, they work alongside them. A mural may spark a question: What stood here before? Who lived here? What was lost? The answers emerge through deeper exploration.

Within this project, murals function in exactly this way. They act as entry points that lead viewers toward oral histories, archival materials, and interpretive narratives, creating layered understandings of memory and place.

Ethics, Accountability, and Community Trust

Throughout the interview, Jackson emphasizes the ethical responsibilities that accompany public art in historically significant neighborhoods. He highlights the importance of trusted liaisons, community leaders, and ongoing communication, especially when artists are working in places where they are not originally from.

Trust, he notes, is built through presence and care—showing up, listening, and respecting local knowledge. These practices help ensure that public art does not reproduce extractive relationships, but instead supports community memory and agency.

This emphasis on accountability aligns with the broader goals of Where Do We Go From Here?, which seeks to foreground ethical interpretation and shared authority in public history work.

Why This Conversation Matters

Abel Jackson’s reflections illuminate how public art can operate as a form of public history—one that engages displacement, memory, and resilience without reducing complex histories to static narratives. His practice demonstrates how artists and historians alike can contribute to conversations about loss and survival in the urban landscape.

As this project expands across cities and communities, Jackson’s insights provide a framework for understanding how creative practice can help preserve what urban renewal attempted to erase: relationships, knowledge, and the enduring presence of Black communities.

“Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”

Oral History with Preservationist, Monique Stubbs Hall

It all begins with an idea.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

“Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.”

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

Blog Post Title Three

It all begins with an idea.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.

Blog Post Title Four

It all begins with an idea.

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Don’t worry about sounding professional. Sound like you. There are over 1.5 billion websites out there, but your story is what’s going to separate this one from the rest. If you read the words back and don’t hear your own voice in your head, that’s a good sign you still have more work to do.

Be clear, be confident and don’t overthink it. The beauty of your story is that it’s going to continue to evolve and your site can evolve with it. Your goal should be to make it feel right for right now. Later will take care of itself. It always does.